The old epigram “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” perfectly describes the paradoxical state of virtual team management. This is also illustrated by the yin-yang symbol. One side denotes inertia and the other side innovation. We will examine how both sides of this divide play out today.

The first “virtual teams” appeared in the 1990s. This was possible due to a confluence of technological advances, evolving management thinking, and a shift in business language. Every decade since WWII has experienced a transformative wave of innovation – personal computers (1960s), cell phones (1970s), voicemail (1980s), Internet, World Wide Web, emails (1990s), and webinar videos (2000s).

This ever-increasing technological capacity is paralleled by ever-widening frames of management perspective, theory, and practice. For example, the very idea of a “business team” is relatively new.

“While work teams were used in the U.S. as early as the 1960s, the widespread use of teams and quality circles began in the Total Quality Management movement of the 1980s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many companies implemented self-managing or empowered work teams. To cut bureaucracy, reduce cycle time, and improve service, line-level employees took on decision-making and problem-solving responsibilities traditionally reserved for management. By the mid-1990s, increasing numbers of companies such as Goodyear, Motorola, Texas Instruments, and General Electric had begun exporting the team concept to their foreign affiliates in Asia, Europe, and Latin America to integrate global human resource practices” (Kirkman et al., 2001).

Even business language has evolved. For example, before WWII, “software” referred to “woolen or cotton fabrics”. The term “virtual” also morphed from a 15th-century philosophical definition – “something in essence but not fact” – to a 20th-century technological definition – “not physically existing but made to appear by software”.

In her book “Virtual Teams”, Jessica Lipnack, a pioneer in the field, described Valent Software’s “virtual workplace” as consisting “largely of cellphone calls, e-mail correspondence and meetings in hotel lobbies. Except for a small office in Woburn, Mass., that it rented primarily as a place to receive mail, Valent did not have a brick of property to its name” (Lipnack, 2004). Another early example was Sun Microsystems, who “had started an initiative called ‘Open Work Program’ in 1998 which supported its employees to work from anywhere and at anytime (telecommuting). By 2007, it led to huge cost savings for the organization, to the tune of $68 million”.

In the decade since Sun Microsystem’s early innovation and success, further advances have continued to make virtual team communication easier than ever. For example, webinar video services like Zoom and team-based platforms like Slack, only a few years old, have further transfigured online team collaboration.

Inertia

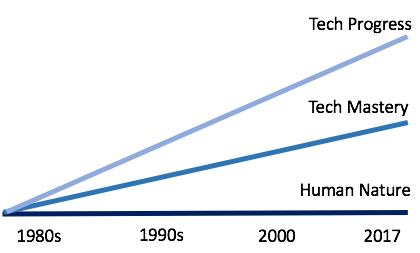

The Latin root of “inertia” originally meant “unskillfulness” as well as “inactivity”. Many organizations resist adopting virtual teaming. Many others, like IBM, have famously rolled back use of remote employees and teams. Other organizations poorly support the introduction of virtual teams. While tremendous technological progress has been made, the rate of adoption and mastery lags behind, as illustrated. Most importantly, human nature remains an unchanged constant. This is the one dimension most resistant to change and most crucial to virtual team effectiveness.

People generally “underestimate the challenges of working with one another through a virtual platform”. Most are therefore unprepared upon joining a virtual team. The result is costly both financially and psychologically. A critical gap exists between the promise and performance of most virtual teams. Research shows that more than 80% of virtual project teams perform poorly and 75% of cross-functional teams are seen as dysfunctional.

“These challenges, of course, can be addressed by promoting strong leadership behaviours and training virtual teams in skills to build relationships and trust while implementing processes and systems that allow them to collaborate more effectively. Unfortunately, according to our own research, these things aren’t happening, at least not at most companies. Simply put, best practices aren’t being implemented (or even clearly defined) enough. In fact, research indicates that less than 20 per cent of virtual teams receive training on how to work effectively as a virtual team, leaving most virtual leaders and their team members operating in unproductive ways. As a result, one-quarter of virtual teams fail to meet expectations”.

Tech Gap

Today’s online resources to help virtual teams collaborate better are ubiquitous, low cost, and easy to use. However, there is a problem in adoption and mastery. “Not knowing how to effectively use the technology available is an issue for at least 1 in 5 virtual teams” (Elvis, statistics and virtual teams | Target Training GmbH).

Even more fundamentally, “Despite the advances and promise of richer collaboration technologies like web conferencing, shared workspaces, private social networks and video conferencing, the traditional means of email (93%), phone and conference calls (89%) still get used most often among virtual team members. When asked if being able to see the remote team member via video would be beneficial, almost three-quarters (72%) said ‘yes’ but only about one-third (34%) actually use video conferencing now” (Untapped Potential of Virtual Teams: A new study by Siemens Enterprise Communications).

Soft Skills Gap

In “Soft Skills are Hard”, the authors undertook a systematic review and meta-synthesis of “more than 6000 academic articles and policy papers written by governments, professional associations and other stakeholders” (2015). They found that Canadian employers across practically all sectors generally believe that university graduates do not possess sufficient soft skills needed to perform effectively in today’s hyper-competitive global knowledge economy. There is also a gap between the perceived economic importance of soft skills and the lack of any formal institutional credentials in supporting or providing consistent systemic training anywhere.

LinkedIn’s 2016 “Soft Skills Report” is sobering. “Hiring managers in Canada find soft skills more difficult to find than technical ones, with 67 per cent admitting they struggle to find candidates with the right soft skills compared with only 49 per cent for hard skills.” Worse, the same report found “that 61 per cent of Canadian hiring managers feel that the lack of soft skills among candidates limits their company’s productivity.” These findings may be extrapolated more generally.

“Soft digital skills are an increasingly important characteristic of a well-rounded digital professional … More employers (59%) say that their organization lacks employees who possess soft digital skills than hard digital skills (51%). As Wendy Murphy, Senior Director, Human Resources, Europe, Middle East and Africa at LinkedIn puts it, “Soft digital skills are required across all levels, especially the ability to learn and to be agile”.

Education and Training Gap

Most education institutions still do not prepare students for the new world of virtual teamwork. “One of the greatest concerns for employers of IT graduates … is the lack of skills required to work effectively within a collaborative IT team”. Later in this article, we will examine several innovative universities that do. There are also few or no incentives for educators to “up-skill”, and this is needed as well.

Academic Research Gap

University research on virtual team dynamics has not kept up either. For example, there is also “little research or literature on how such teams are formed for the purpose of learning”. It is also “staggering how little research there is about conflict resolution strategies in virtual teams”.

Innovation

Despite the inertia within wide swaths of organizational life, a new dimension of knowledge, praxis, and learning is emerging regarding the field of virtual team management. This includes an evolving set of rubrics, standards, and metrics. A good analogy is the field of project management with its PBOK. Indeed, virtual team management and its associated competencies will ultimately become rationalized in the same way but in much less time. We see two interrelated trends in virtual team management innovation within education and business respectively.

A number of universities around the world, often in collaboration with corporate partners, have begun introducing new courses and workshops in virtual team management and leadership. (These include: INSEAD, McGill University, Yale University, and Stanford University.) Faculties and departments in business, engineering, design, and public relations have all developed tailored programs.

These vary in duration, content, cost, and location, i.e. in person, online, or in combination. For example, in January 2016, the Yale School of Management introduced its first virtual team management course. This is now mandatory for its MBA students. Harvard University’s own new “Managing Virtual Teams” promises it “will teach you the people skills that you need to create high performance virtual teams”.

Most of these programs have a strong experiential, interactive component. As Harvard University’s course description states, “The best way to learn about virtual teams is to participate in one”. Three broad dimensions of high-performing virtual teams – Task, Social, and Technology – are addressed in most programs. This involves use of concept models, and practices adapted from project-based learning, problem-based learning, peer-assisted learning, and work-integrated learning.

As well, new graduate attributes are being aligned with enhanced requirements from various professional accreditation bodies. For example, the University of South Queensland, already a pioneer in distance education, has helped establish global performance standards for engineers working on virtual teams.

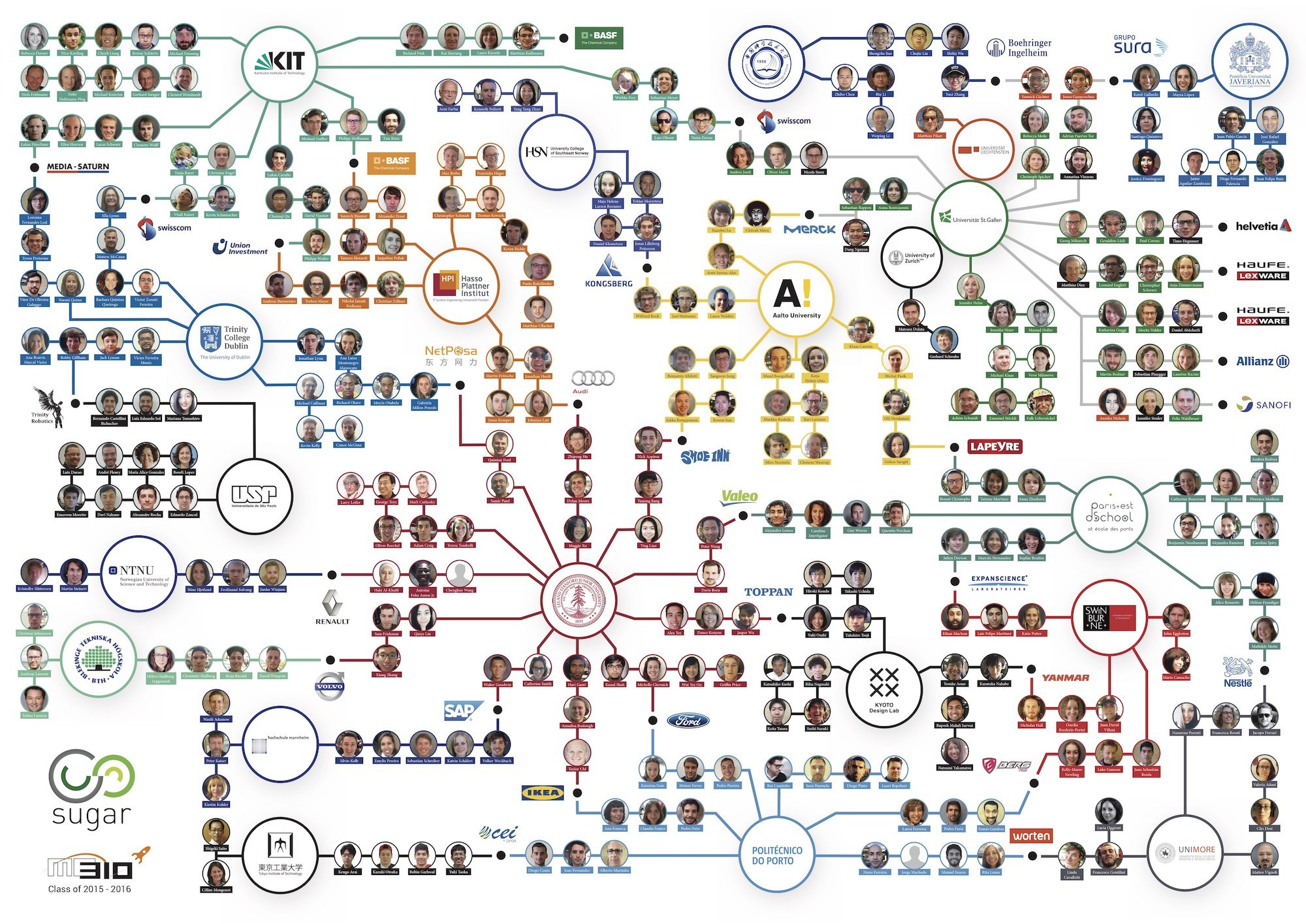

It is also worth noting there are several distinct innovative global cross-university initiatives for student virtual teams in engineering, design, and public relations. They all share a common goal. That is for participants to develop a broad range of global skills by collaborating and competing with their peers in other universities around the world. For example, design faculties participate in: “Sugar … a global network that brings together multidisciplinary students from different universities and challenges them to solve real world product development challenges” .

A number of corporations invested in adopting virtual team management early on. They have also innovated new best practices and generated new research literature. For example, in 2011 Siemens Enterprise Communication (now rebranded as Unify) published “The Untapped Potential of Virtual Teams”. It recommends “Shifting focus … from ports to people … Enterprises should move from concentrating on delivering communication devices connected to a technology platform, to a focus on the user experience and enabling high performing teams to collaborate”.

In “Virtual Environments Innovation and R&D Activities: Management Challenges”, the authors conclude “that managers of companies should invest less in tangible assets, but more in R&D and virtual teams to generate knowledge, and in their employees’ creativity to stimulate incremental innovations in already existing technologies that will directly generate their future competitive advantage”.

Jessica Lipnack, a pioneer in the field of virtual team management, stated the following in 2004. “We are untrained for life and work in the fluid, instantaneous global ‘village’. Thus, we need new models for teams that also incorporate the timeless features of working together.” However, 13 years ago, the technology was not yet robust enough to enable “virtual strangers” around the globe to become effective virtual teams without ever meeting in the flesh.

Now it is. Innovative individuals and organizations are making use of the full range of psychological and technological resources widely and inexpensively available. A 2016 Deloitte survey of C-suite executives reports that the majority (72%) “see virtual teaming capabilities across cultures as becoming significant and normative in the next five years.”

For the laggards, and those who refuse to acknowledge the need for relevant training support, John Chambers, Cisco’s Executive Chairman, had a blunt message several years ago in light of this rising tide. “Globally linked virtual teams will transform every government and company in the world. Any of our peers who don’t do it won’t survive” (DeRosa, 2010).