At Cactus, we actively encourage our engineers to explore emerging technologies and share the tools that really impact the way we build, automate, and think about systems.

During that ongoing exploration, OpenClaw quickly became a topic of conversation across the team. Not because of flashy demos or big marketing claims, but because of what it represents: a local-first, agent-based runtime that actually executes tasks, integrates with real systems, and lives on your own hardware.

In this article, Pablo Huet, Full-stack Developer at Cactus, shares his experience running OpenClaw on a Raspberry Pi 4 and reflects on what surprised him, what worked in practice, and what this kind of always-on agent might mean for the future of practical automation.

Introduction

“The weird part wasn’t that it could run commands. The weird part was that it sometimes acted like it wanted to.”

That’s what surprised me after installing OpenClaw on a Raspberry Pi 4 and letting it live in my home lab for real tasks.

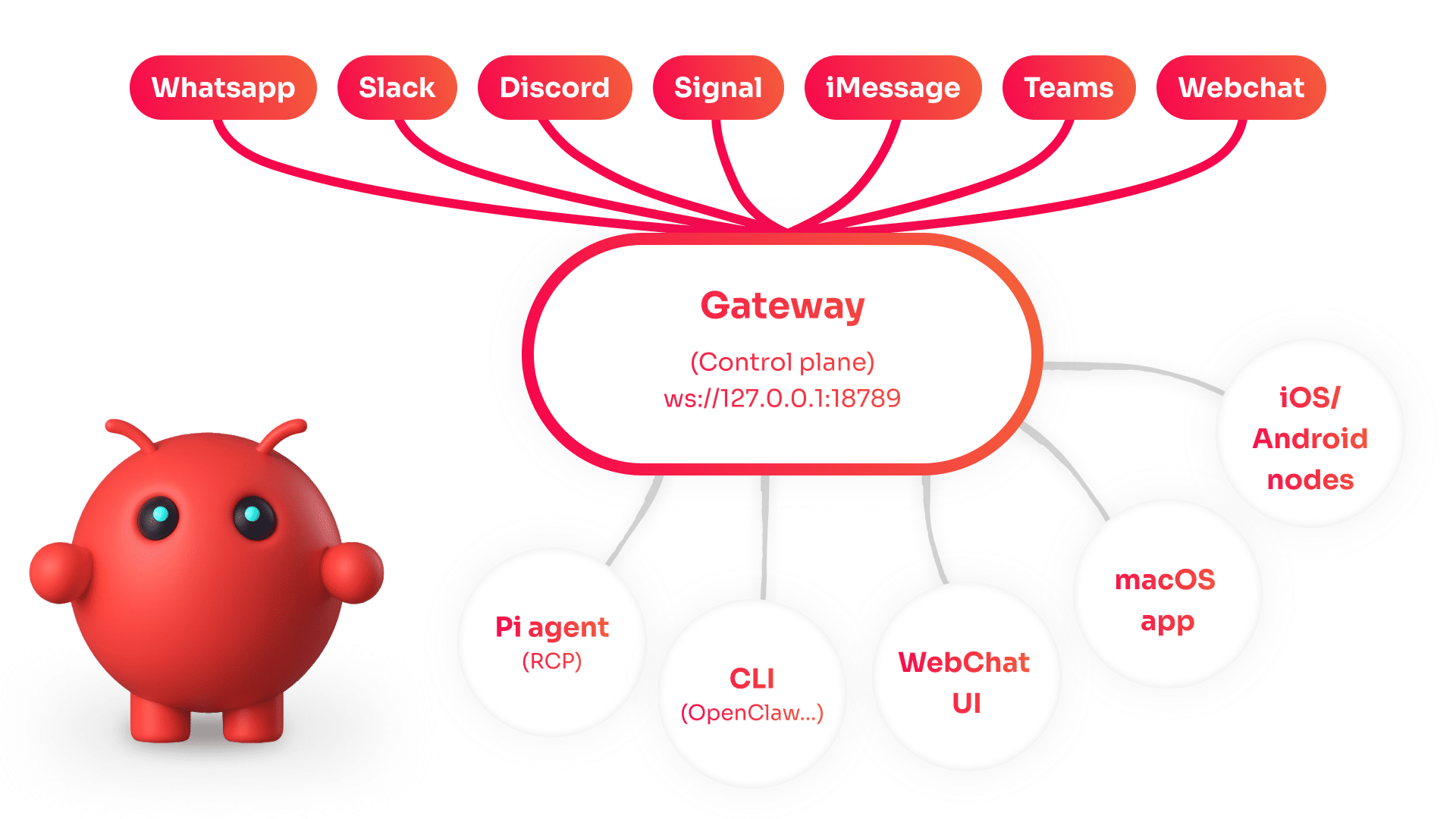

OpenClaw is a self-hosted personal AI assistant that you run on your own hardware. It has a Gateway that connects your chat apps (WhatsApp, Telegram, Slack, Discord, iMessage, etc.) and routes work to “agents” that can use tools, read files, and run shell commands. Open source, MIT licensed, and despite being fairly new it already sits at 178k stars and 458 contributors on GitHub. The thing is growing fast.

Installing it is really straightforward. You run one command, the onboarding wizard pulls everything in, and all you need to do is drop in the API keys for whatever model you want to use. Five minutes, tops.

Now, here’s the thing: once installed, OpenClaw has unrestricted access to the entire system. So you really want to run it on a machine you don’t care too much about, or a properly isolated VM. In my case, I put it on an old Raspberry Pi 4 with 4GB of RAM that had been sitting in a drawer.

Why this feels different

An assistant available around the clock

What surprised me most about OpenClaw is how it shifted my whole relationship with language models. It stopped being a help desk or a fancy autocompleter. It turned into something closer to a very smart assistant you can hand any task to, and it just goes off and does it. No supervision, no babysitting. A black box that plans and executes on its own.

One of the first things I asked it was to find cheap travel deals, just to see what I was dealing with. I didn’t expect much. But less than thirty minutes later it came back with a detailed report: dates, destinations, prices, even optimized for total travel time. All nicely formatted in a Markdown file. When I looked at what it had actually done under the hood, it had built a whole system of scrapers by itself, crawling multiple flight search engines to extract the data. I hadn’t told it how to do any of that.

A simple chatbot on the surface

OpenClaw comes with integrations for Telegram, WhatsApp, Discord, Signal, and others out of the box. So from the outside, interacting with it is just a regular text conversation. It understands text, audio, and images, and can send files or whatever it generates back to you.

But underneath, it’s way more than a chatbot. Because it has access to its own system, it can basically adapt to and integrate with anything you point it at. It just writes code and understands language and binaries, what can go wrong?

The problem: automation is still fragmented

Even in 2026, most of us still glue workflows together with:

- Shell scripts nobody wants to touch

- Alerts that trigger humans, but not any action

- “Smart” assistants that are cloud-only and hard to trust with real access

Agent-style assistants promise something different: the ability to take actions, not just answer questions. But most of what we’ve seen so far were sandboxed demos or API toys. OpenClaw is one of the first I’ve used that feels like it was designed to actually live somewhere.

The opportunity: a local, always-on “ops sidekick”

What makes OpenClaw interesting is that it’s local-first (your hardware, your rules), multi-channel (one Gateway feeding WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, Slack, Signal, iMessage, Teams, all at once), and it actually does things: shell commands, web browsing, file access, external integrations. It’s not a wrapper around a chat API. It’s an agent runtime with real tool use, sessions, and memory. (GitHub)

Of course, that power comes with real security tradeoffs, especially around “skills” (the extension system) and prompt-injection risk. The security docs are pretty honest about this, which I appreciate (OpenClaw Security).

Under the hood

Gateway + Agents + Skills

The architecture is actually pretty simple once you see it:

The Gateway is the control plane. Sessions, routing, channel connections, cron jobs, webhooks, even a browser-based UI, all flow through a single WebSocket on port 18789.

Agents are isolated work contexts, like separate brains per workspace or sender. Each one has its own session history, workspace directory, and tool permissions. You can run a personal agent with full access and a family agent with read-only tools on the same machine.

Skills are folders with a SKILL.md file that teach the agent how to use a tool or service. YAML frontmatter, some instructions, done. You can use the bundled ones, install from ClawHub (a public registry), or write your own in the workspace.

Visually it’s something like this:

My hardware choice: Raspberry Pi 4 (4GB)

This is not a GPU box. That’s the entire point.

The Pi doesn’t run inference locally. It runs the Gateway and the agent runtime, and those call out to cloud models via API (in my case, Claude Opus 4.5 through Anthropic). The heavy lifting happens somewhere else; the Pi just manages sessions, handles messaging, and executes tools. 4GB is plenty for that.

In practice, I had it running the Gateway 24/7, keeping Telegram connected all day, executing scripts, manipulating files, scraping the web, calling APIs, and talking to physical devices on my network. No issues.

There’s a small community of people running OpenClaw on everything from Mac minis to Pis, all chasing the same thing: always-on without a full server. There are even dedicated Pi installation guides floating around.

A practical note on security (because it matters)

OpenClaw’s security documentation is probably the most honest I’ve come across in an open-source project. They literally open with:

“Running an AI agent with shell access on your machine is… spicy. Here’s how to not get pwned.”

And they’re right. Your assistant can run shell commands, read and write files, access the network, and message anyone. And anyone who messages it can try to trick it into doing bad things.

The way they think about it is: first decide who can talk to the bot (pairing, allowlists). Then decide where it can act (tool permissions, sandboxing). And only then think about the model, because you should assume the model can be manipulated and design so that manipulation doesn’t blow up everything.

This isn’t just theory either. Malicious skills already appeared on ClawHub targeting crypto users, so be careful when giving your friendly lobster bot access to anything with real money attached.

Letting It Run

What I installed and how it behaved

Setting it up was quick: Node 22, npm install -g openclaw@latest, then openclaw onboard –install-daemon. The wizard takes you through model selection, channel pairing, and service installation. I locked the Gateway down to localhost, connected only Telegram, and set DMs to pairing-only.

After that, I just started talking to it the way you’d talk to a colleague who happens to live inside a Raspberry Pi:

- “Write a script that monitors this endpoint and alerts me on Telegram if it goes down”

- “Organize these photos by date into folders”

- “Find me the best flights to Lisbon in March”

- And one memorable integration: my LED panel

The Pixoo64: a “physical UI” for an agent

I happen to have a Divoom Pixoo-64 — a 10.3″ Wi-Fi pixel art frame with a 64×64 LED matrix. It’s basically a tiny wall dashboard, but friendlier in some ways.

To control it programmatically, I wrote Pizzoo some time ago, a Python library for Pixoo64-style matrix displays with support for animations, drawing primitives, XML template rendering, and even a mini game engine:

I simply gave OpenClaw the PyPI link, the template docs, and the device’s IP address through a Telegram message. Three minutes later, it had installed the library, read the docs, written a Python script using the template system, and pushed a “Hola :)” to my display. No hand-holding, no debugging, no back-and-forth.

And then it just… kept using it.

The “pseudo-conscious” bit

At some point, the agent started doing something that felt odd.

It would send things to my Pixoo64 without me asking. A weather update in the morning. A little animation when a scheduled task finished. Once, a pixel art lobster (its mascot is a space lobster named Molty 🦞).

I’m not going to claim anything mystical. There are normal explanations for all of this: OpenClaw has cron jobs and webhooks built in, so the agent can schedule follow-ups on its own. Once it used Pizzoo successfully, that tool became part of its known capabilities, so it could decide to use it again whenever it made sense. LLMs write as if they have intent, and we read intent into it naturally. “I thought you’d like to see the weather” is just a string. But it feels like thoughtfulness.

And then there’s the persistence factor. When something runs 24/7, has a name, has a personality file (SOUL.md is a real thing in OpenClaw), and can push pixels to a physical object on your wall… it stops feeling like a chatbot.

It’s not conscious. Obviously.

But I’ll say this: when you combine always-on runtime, a physical display, the freedom to execute small actions, and a personality that carries across sessions, you get something that feels like it has agency. And that feeling is interesting, because I think that’s actually the product space worth exploring. Not AI that answers questions, but AI that has somewhere to live and something to do.

Conclusion

What I think this points to

OpenClaw connects dots and tools that don’t normally talk to each other, automating the small ops tasks nobody wants to write a script for, making systems more interactive without having to build a whole platform.

The idea of a local Gateway that bridges your messaging apps to an agent with real tool access feels like it’s in the right direction. That said, capability and risk grow together. The more you let an agent do, the more you need to think about least privilege, auditing extensions before enabling them, keeping channel access tight with pairing and allowlists, and generally knowing what the worst case looks like before it happens.

Closing thought

Running OpenClaw on a Pi 4 made one thing clear: if you give an agent a stable home, a few tools, and a way to touch the real world, even if it’s just a 64×64 LED display, it stops feeling like chat and starts feeling like infrastructure.

And when it sends you a pixel art lobster at 7:00 AM just because it can, you start wondering where exactly the line between “tool” and “companion” is.

Thanks to Pablo for taking the time to experiment, document, and share his findings with the Cactus team.